Red

Easter

Easter has no fixed abode; this most

important movable feast of the Orthodox Christian year flies

like a shuttle between March and May and weaves the diverse

important dates into a single metaphysical narrative. In the

memorable year 2000, it coincided with the Western Easter

proclaiming Christendom’s underlying bedrock unity. Last year,

Good Friday fell on April 9, the Deir Yassin Massacre Day, when

apostles’ children were slaughtered by Jewish terrorists in the

land of Christ. This year, Resurrection Sunday comes on May Day,

weaving back the unnecessary tear between the Reds and the

Christ. The Russians, amongst whom I celebrate today, christened

it Krasnaya Pascha, “Red Easter”.

In this unique country – nay, civilisation, -

thousands of men and women stand up for the all-night-long

Easter service and in the morning join mass demos under the Red

banner. Thus for me, and for many Russians, May Day came as a

second, unexpected apotheosis of the Easter celebration.

I came to Russia for the last weeks of their

Lent and for Easter. The Spring was unusually long and cold;

until recently, white snow covered the eternally green boughs of

the pines and the naked white bodies of birches in the forest.

Thick ice allowed fishermen to drill holes and catch fish in the

frozen streams until mid-April. It was good: Russia is beautiful

like a bride in her white dress of snow and ice, while

rosy-cheeked and blue-eyed Russian girls in their modest fur

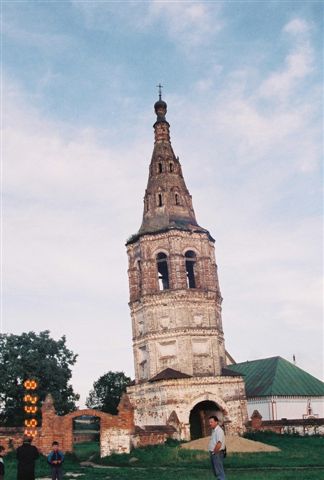

coats are irresistible on frosty days. And the churches with

their multicoloured onions and domes are embellished with

exquisite icons and frescoes.

In

Soviet days they served as coal stores, hardware shops, or at

best, museums of atheism. Active churches were a rare thing. The

rest was so run-down that they inspired no interest -- just

dirty old structures ready to be demolished when a new bypass

has to be built. And a lot was demolished. Since 1991, the

Church embarked on a huge project of regaining surviving

churches and repairing them. The result is mind-boggling –

yesterday’s Cinderellas became today’s Princesses. I could not

recognise them – their old domes a-blazing with gold plating,

bells a-ringing, and interiors totally redone. The surviving

frescoes were lovingly restored, ruined ones were painted anew

in the traditional Byzantine style. The monasteries turned into

soldiers’ barracks or boarding schools for young delinquents

returned to their original purpose and many serious young and

spiritual Russians take up the Orders. Even the long-demolished

Cathedral of St Saviour in Moscow – a site of a swimming pool in

Soviet days – was rebuilt. Thus the Russians succeeded where the

Jews failed: they did rebuild their Temple. In

Soviet days they served as coal stores, hardware shops, or at

best, museums of atheism. Active churches were a rare thing. The

rest was so run-down that they inspired no interest -- just

dirty old structures ready to be demolished when a new bypass

has to be built. And a lot was demolished. Since 1991, the

Church embarked on a huge project of regaining surviving

churches and repairing them. The result is mind-boggling –

yesterday’s Cinderellas became today’s Princesses. I could not

recognise them – their old domes a-blazing with gold plating,

bells a-ringing, and interiors totally redone. The surviving

frescoes were lovingly restored, ruined ones were painted anew

in the traditional Byzantine style. The monasteries turned into

soldiers’ barracks or boarding schools for young delinquents

returned to their original purpose and many serious young and

spiritual Russians take up the Orders. Even the long-demolished

Cathedral of St Saviour in Moscow – a site of a swimming pool in

Soviet days – was rebuilt. Thus the Russians succeeded where the

Jews failed: they did rebuild their Temple.

The last days of the Holy Week were quite a

build up. The churches were full day and night; the believers

formed long queues to go to confession: the Russian church has

no booths for this purpose, and confession is a face-to-face

interview in a nave. Only after a three-day fast and confession

one may receive the communion done with bread and undiluted

wine, as in the church of Apostles. Besides the Communion, the

Orthodox church also practice pre-Paschal unction reserved in

the West only for the dying.

On Easter Saturday, Russian ladies baked

their delicious Easter cakes and brought them to be blessed by

the priest in the church, so in the afternoon the church

compound was scented by spices, raisins and fresh dough. It is

their custom to break the fast by eating these sweetish cakes

with cottage cheese.

The night-time Easter service was very long,

but people did not leave early – they felt it was the

much-expected culmination of their long and hard Lent. Indeed,

Orthodox Lent is very strict: even olive oil (do not even think

of dairy or fish) is permitted on Sundays only, while marital

joys are banished completely. I went to a church of a nearby

monastery, a vast structure built in the beginning of the 20th

century in Art Nouveau style with pre-Raphaelite frescoes, and

stood all night long, until the dawn, among throngs of smartly

dressed Russians with lit candles in their hand who answered the

priest calling out ‘Christ is Risen!’ with their thunderous

‘Indeed, He is Risen!’

And just a few hours later I stood opposite

the Bolshoy Grand Opera (where I was recently at the premiere of

a specially commissioned by the theatre new opera

Blumenthal’s Children, a fascinating and provocative

treatment of the iconoclast Sorokin’s writing by St Petersburg

composer Desyatnikov) in the May Day demo crowd, listening to a

Communist leader who repeated just the same call; and from under

the Red banners came a reply: “Indeed, He is Risen!”

Paradox? Not really. Even universal faiths

have some local colour, and Russian Communism and Russian

Orthodox Church share the same background. On every turn of

their development, whether in their old Pravoslav Tsardom, or in

the Red Republic, the Russians who strove for the unity and

brotherhood of Man were motivated by compassion and acceptance

of “losers.” They consistently rejected Mammon. The Russians

despise money and material belongings; for them, poverty is a

welcome sign of an honest man rather than a mark of social

leprosy as in the West. They suspect rather than admire a

moneybag. The old adage of ‘the Spiritual East’ as opposed to

‘materialistic’ West still holds true: who does not like East,

does not love the Spirit.

Today, Russian Reds are reconciled with the

Church; the Communist Party members attend the services and

joined the Pravoslav tradition. Gennady Zuganov, the CPRF

leader, congratulated the demo with the May Day – and with

Christ’s Resurrection as well. Rogozin, the leader of a

breakaway Rodina faction, now a big party by its own right, was

even more eloquent in referring to Easter. As various Red and

nationalist parties and groups represent a clear majority of the

Russians, it is an important and a positive change from the days

when churches were dynamited and worshippers discouraged.

It is a good change, for the Reds’ loss of

power can’t be understood but in context of Russian spiritual

quest. The Russian Communists modernised Russia, they created a

society of mutual support. They could not give villas and

Cadillac cars to everybody, so they gave what they could.

Everybody had more or less the same: they had their safe and

assured employment, their free accommodation, free electricity,

telephone, heating, public transport.

But they forgot to attend to spiritual needs

of the Russians. They forgot the teleological ‘What for’. And

people can’t live without a purpose. This lack of purpose became

obvious when the pressing material needs of the people were

satisfied. The Russians accepted Communism – not in order to

live better; they had a greater goal of spiritual perfection.

The trouble began from the top: the de-spiritualised Soviet

elites of the last decades drifted to the right; they loved

Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan, and had accepted the

neo-liberal world-view a long time before the collapse.

Indeed, in the West, the neo-liberals solved

the problem of “What for” by creating massive social insecurity:

people are not liable to think of spirit if they can be thrown

out of their homes by a bank. Gorbachev copied their solution

when he allowed the Soviet ship to capsize. He was supported by

the pro-Western reformers.

The West is full of variety and contains many

ideas and paradigms. But the Russian Westernisers were a

narrow-minded lot; they embraced the Chicago school of Milton

Friedman with fervour; and despised the Russian people, their

history and tradition. They privatised Russian national

property, sold it to the trans-national companies and tried to

integrate Russia as a supplier of raw materials. However, their

victory was not as final and conclusive as they thought.

There are clear signs of Russians reasserting

their history after the clean break of 1991. It is not only

churches lovingly restored and filled with worshippers; not only

restoration of historic names – thus Kalinin Avenue (named after

a Soviet leader) became again the Invention of the Cross street.

It was done by the winners of 1991. But the Soviet past is being

reintegrated, too. The great celebrations of V-day due on May, 9

are a sign of the change. The liberal reformers of 1991 asserted

that there was no difference between the Commies and the Nazis,

between Hitler and Stalin. They mocked the veterans saying “Pity

you weren’t defeated: we would live like Germans”. They forbade

celebrations of V-day: not out of love to Hitler, but because of

their hate to the Soviet anti-Mammonite past.

This year, every street in Russia bears some

congratulatory poster blessing the vets for their great victory.

Here again, it is not a sign of hate to Germany or to National

Socialism, but of reconciliation with the Soviet past. At the

May Day demo, Stalin was acclaimed by Zuganov and other

Communist leaders as ‘the father of the great victory’. There

were his portraits a-plenty. It’s not that the Russians miss the

Gulag or industrialisation; but Stalin and his rule are part and

parcel of Russian history. Likewise, the French Restoration

regime of Louis the Eighteenth called Napoleon ‘the Corsican

Monster’, but just a few years later, by 1840s, the late Emperor

regained his place in the Pantheon of France.

The struggle for Russia's future is far from

over; it has just started. Some people may think that this great

country became an irrelevancy, a rusty oil pipeline and a

consumer of Chinese goods and American ideas. But Russia is

alive: Russians write great books still unknown in the West.

Three books of the last decade, The Last Soldier of the

Empire by Alexander Prochanov, The Blue Lard by

Vladimir Sorokin and The Sacred Book of Werewolf by

Victor Pelevin are as enjoyable, challenging and uplifting as

Hundred Years of Solitude by Marquez. There are no

contemporary writers or books in the West of a similar stature.

In a properly arranged world, these treasures of spirit would be

considered among great achievements of mankind. Indeed, who

cares for oil – it is Russian writing that we should import!

Russians do read a lot. Another positive

change since the Soviet days is freedom of creativity and

publishing. In Soviet days, stifling Party control blocked

incoming ideas and books and stopped their creation in Russia.

Even revolutionary Marxist books were banned, unless written in

boring Sovietese. Now, in a tiny bookshop in a Moscow

Underground for a few roubles one can buy new editions of Guenon

and Joyce, Murakami and Pavic, St Augustine and Chesterton – and

certainly, the Russian writers and philosophers old and new,

with their fusion of metaphysics, theology and politics: from

pre-revolutionary Bulgakov, Florensky, Rozanov to contemporary

Alexander Dugin, Serge Averintsev and Alexander Panarin. I felt

myself as Gulliver in Brobdingnegg, the Land of Giants: there

are hundreds of Russians one can discuss most complicated

questions with and find oneself out of one’s depth.

Russians are aware of their problems and

think of new solutions. Their problems are our problems, too:

the Soviet collapse coincided with (or ushered in) the global

Ice Age of social deep-freezing. More and more people in the

once-protected West find themselves marginalised; the Third

World outpoured unto New York and London; compassion is

outlawed; spiritual search is non-existent.

The recently demised Russian thinker

Alexander Panarin believed that the Orthodox Christian paradigm

has a way to deal with the coming neo-liberal Ice Age by

bringing in the Christian Eros as the force to revitalise the

Universe. Russia may yet raise again the banner to summon the

defeated, the outcast, the disenfranchised, the discarded

against the new Masters of the World, he wrote.

In his view, Orthodox Russian Christianity is

different and can offer a solution to perplexed mankind because

it is centred on the Lady. Indeed, Her image occupies the place

usually preserved for the Cross in the Western churches. She is

often presented as the Queen sitting on the throne with the

crowned Child on Her lap. For the Russians, the Mother of God

represents Nature. She is divine, connected with the Spirit and

bears Him in Her womb. The Russians’ love to Christ who is

Spirit is not divorced from their love to the Lady who is Mother

Earth and their Compassionate Intercessor. God the Father, the

God of Old Testament, the God of Justice has very little

presence in the Russian universe.

If Dan Brown were to visit Russia, he would

never write his Da Vinci Code, for the female divinity is

not suppressed or replaced here. In his very American

bestseller, the Catholic Church tries to suppress the cult of

Mary Magdalene as it is afraid of femininity; while the Jews (of

all people) protect and guard Mary’s remains. In real life, Jews

have no female saints and dislike Our Lady even more than they

dislike Her Son, while the Church venerates the Lady and adores

the female saints. But Dan Brown had to fit his perfectly

normal, true and justified longing for the Earth-bound and

Spirit-connected Mediatrix into the Judaeo-American

neo-Calvinist picture of the world, where Jews are always right

and the church is always wrong. That is why he turned everything

upside down; the New York Times spread its fame and the

public bought it. In Russia, he wouldn’t be able to

misrepresent: here, the Lady reigns supreme, and the ideas of

Compassion and Connection to nature and spirit wait to be

unleashed.

II

Will it happen? Russia is at the crossroads.

While new-found freedom of creativity, publications and

religious freedom are very important achievements, probably they

could have been had without the great social cost the Russians

were forced to pay. Their national assets – from oil and gas to

land and factories – were privatised and taken over by a small

group of extremely well-connected oligarchs. Now Western

companies try and buy these assets. Russian industry is in poor

shape; de-industrialisation proceeds unhindered. Once an

advanced country of great science and modern industry, Russia is

being converted into a raw materials’ supplier. Though oil money

makes this decline relatively comfortable for many Russians, in

case of economic downturn catastrophe is inevitable.

Russians feel themselves threatened by the

aggressive US drive to acquire military bases and political

influence in the ex-USSR republics. The Orange revolution in the

Ukraine and the possibility of NATO forces entering this Slav

hinterland made the threat acute. Russian James Bonds, Putin’s

ex-colleagues from St Petersburg branch of the State Security,

are strongly represented in the state apparatus; usually such

people – like George Bush the Senior – are considered patriotic

chaps, but now the Russians are worried not only by their lack

of liberalism and corruption, but also by their inability to

meet the American challenge and their readiness to give in to

American demands, including the much discussed question of a US

presence at Russian nuclear facilities. The media is

concentrated in a few hands; though as opposed to the West,

there is a prominent state-owned media, but it is also quite

pro-Western or provides poor-quality entertainment.

At the May Day demo, the Reds demanded just

one hour a day on the state TV to be devoted to their

programmes: this exceedingly humble request is not likely to be

met. Meanwhile, TV broadcasts Swan Lake and concerts of rock

groups, while political discussion is kept under wraps. The Reds

and the Nationalists are unhappy with the regime, for it is not

doing enough to stop embezzlement, corruption, privatisation,

de-industrialisation and impoverishment of the people. Though

the regime took up some of their slogans, their words remain

words only and are not accompanied by action.

But the Reds and the Nationalists are not in

fighting shape. They were defeated in 1993, when Yeltsin shelled

the Parliament and took dictatorial powers. In 1996, the Red

leader Zuganov actually won the presidential election, but the

results were falsified, and Zuganov did not dare ‘to do a

Yushchenko’ and forcibly take what was his by right. Since then,

the Reds suffer from a certain weakness. This could change

because of an alliance with two outsider groups.

A

new force, National Bolsheviks led by Edward Limonov, a

charismatic poet, are anything but vegetarian. Very young,

practically teenagers or in their early twenties, the NBP made a

few spectacular actions: takeovers of ministries and even of the

President public reception office. They carry out an unusual

form of ‘terror’ – instead of bombs, they throw eggs, rotten

tomatoes and pies, slapstick-comedy-style, into politicians and

officials’ faces. The authorities were duly terrified and meted

out a five-year jail sentence for a well-aimed pie. Some forty

NBP young men and women are now in jail, but their readiness to

go into action where others just talk made them the cutting edge

of the opposition. They are courted now by Communists and

Liberals alike. At the May Day demo, Limonov was standing next

to Zuganov and Rogozin, leaders of much bigger parliamentary

parties. A

new force, National Bolsheviks led by Edward Limonov, a

charismatic poet, are anything but vegetarian. Very young,

practically teenagers or in their early twenties, the NBP made a

few spectacular actions: takeovers of ministries and even of the

President public reception office. They carry out an unusual

form of ‘terror’ – instead of bombs, they throw eggs, rotten

tomatoes and pies, slapstick-comedy-style, into politicians and

officials’ faces. The authorities were duly terrified and meted

out a five-year jail sentence for a well-aimed pie. Some forty

NBP young men and women are now in jail, but their readiness to

go into action where others just talk made them the cutting edge

of the opposition. They are courted now by Communists and

Liberals alike. At the May Day demo, Limonov was standing next

to Zuganov and Rogozin, leaders of much bigger parliamentary

parties.

The second force is quite different. These

are a mixture of liberals and neo-liberals. Their numbers are

tiny, their two parties could not even make it to the

Parliament. They also had a demonstration on May Day at some

distance from the main event; it was attended by two or three

dozen people. But they have a lot of money and strong positions

in the media, business and power structures. They are also

dissatisfied with Putin; they want to speed up privatisation,

open the country for foreign investors, privatise social

housing, bring in immigrants, remove limitations of free

movement within Russia, withdraw from Chechnya and win release

of UKOS boss Hodorkovsky.

Though their demands are the very opposite to

those of the Reds and the Nationalists, there is a tentative

coalition of these groups against the President. The Reds and

the Nationalists feel they can use some of the Liberals’ media

access and money to advance their agenda; the Liberals need the

masses mobilised by the Reds and the active fighters of NBP. In

return, NBP dropped its more radical slogans and now speaks for

greater freedom and democracy, for amnesty and general softening

of oppressive policing.

All sides in the new setup believe in their

ability to come out the top dog. The liberals are certain they

will eventually get the power in the land; but so do the Reds

and the Nationalists. The liberals have a precedent of the

Ukraine to go by. There, Communists and Nationalists supported

Yushchenko and installed pro-American neo-liberal regime. In

case of a revolution, the liberals will rely upon their

connection with the West, their media power and political

sophistication.

That is why some opposition forces in Russia

prefer to support the President as the lesser evil. These

supporters of the President include Left.ru, our Moscow friends,

a very good left group, and the “Eurasia” of Alexander Dugin, an

important and much admired Russian Orthodox thinker. They feel

that the revolution will be utilised by their enemies, and the

enemies of Russia. They say that they already tried to support

the liberal agenda in 1991, and this experience cured them from

entering such alliances.

Their opponents say that the President is

under American control anyway; he gave up the Russian positions

in Cuba and Ukraine, Georgia and Vietnam. He carries on

privatisation. Though he speaks like a Red nationalist, his

actions follow the liberal blueprint. They also feel that an

‘Orange’ revolution is inevitable: the Americans are fomenting

it, and ordinary people are dissatisfied with the regime. With

the support of the liberals, they can create instability and

hope for the best. “Let us enter the melee,” as Lenin used to

say, “and sort out our strategy later”.

Their slogan is ‘After February, October’ – a

reference to the events of fateful 1917. The Bolsheviks did not

overthrow the Tsar as is sometimes claimed; it was achieved by

the liberal Westernisers who seized power in February 1917 in

order to introduce full-blown capitalism in Russia; but the

Russian soul had a very strong faith-based rejection of Mammon.

Thus a few months later, in October 1917, the Bolsheviks kicked

the Mammonite liberals out. While now the liberals intend to

replicate their Ukrainian success, their tactical partners hope

to repeat the 1917 feat. It is not impossible: Even a few months

before it occurred, nobody expected the Bolshevik victory of

October 1917. Indeed, the liberal revolutionaries, the victors

of the February revolution, were well-positioned to rule. In

order to win, the Bolsheviks cooperated with the German General

Staff, with New York Jewish bankers and even with British

Intelligence – but in the end they dispatched their yesteryear

supporters without a thank you.

It is a dangerous game, but revolutions

usually are. Should we be satisfied with the ‘lesser evil’ or

may we try and gain the whole lot? I have no clear-cut answer.

While a return to Soviet Communism is as unlikely as restoration

of the Pravoslav Empire, the creative forces of the Russians may

still move mankind forward, out of its present impasse. The

divine spark in Man’s soul is not easy to extinguish, the Spirit

will win as sure as Christ is Risen.

Resurrection Sunday 2005, Moscow

|