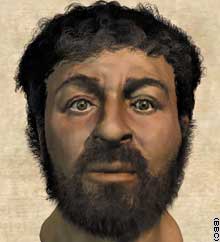

How

did Jesus look - like that according to "Israeli and

British forensic anthropologists and computer

programmers" (see http://archives.cnn.com/2002/TECH/science/12/25/face.jesus/

The

Washington Post printed in its 2002 Easter edition on

the first page (not far from its usual glorification of

Israel

) a feature called ‘The Face of

Christ’, containing a police-style e-fit. It showed a rather

crude and brutish face of a man, with low forehead, darkish

skin, eyes expressive of cunning, a type of lowly menial

worker. It bore a caption, ‘Face of Christ’. Bold

headlines advised the reader that now the latest tools of

science were used in order to find out how Jesus Christ

looked, on basis of some sculls found in

Jerusalem

. Well, 90 p.c. of the

readers

hip does not go beyond the bold headlines,

into petite letters, and they would remain with a feeling that

after all, a scull of Jesus was discovered, and he turned out

to be quite an unpleasant fellow.

The

Washington Post printed in its 2002 Easter edition on

the first page (not far from its usual glorification of

Israel

) a feature called ‘The Face of

Christ’, containing a police-style e-fit. It showed a rather

crude and brutish face of a man, with low forehead, darkish

skin, eyes expressive of cunning, a type of lowly menial

worker. It bore a caption, ‘Face of Christ’. Bold

headlines advised the reader that now the latest tools of

science were used in order to find out how Jesus Christ

looked, on basis of some sculls found in

Jerusalem

. Well, 90 p.c. of the

readers

hip does not go beyond the bold headlines,

into petite letters, and they would remain with a feeling that

after all, a scull of Jesus was discovered, and he turned out

to be quite an unpleasant fellow.

Only

careful perusal of the feature article shows the face being a

reconstruction of a Jewish contemporary of Christ, based on a

few sculls found in

Palestine

. The authors could call the brutish e-fit,

‘The High Priest of Jews’. They could remain neutral and

unbiased and call the e-fit ‘a face of a Jewish (?)

contemporary of Christ’, but they preferred the misleading

legend ‘Face of Christ’, with its implication that Christ

actually looked like a low criminal.

Now the Die Welt correspondent in Rome, our friend Paul Badde,

found another, more likely image:

The

true face of Jesus

by

Paul Badde

What

did Jesus look like? A bit like Jim Caviezel

in the film "The Passion of The Christ"? Like

the portraits by Durer and El

Greco and other artists, which hang in the Palace of the Pope?

But none of these artists ever saw Jesus. What did he really

look like? To these questions, there is an old, old answer: it

is the image contained on a cloth which represents the

"true face" of Christ -- an image even the Pope has

never seen. And this is something which can hardly be spoken

about in the

Vatican

.

This

image is different from all other works of art. Up until the

year 1600 A.D. it was kept inside the old St. Peter's Basilica

built by the Emperor Constantine. Millions saw it there. Since

the early 1600s, however, this "true icon" (the

literal meaning of “vera icona”

which initially formed the name "Veronica") has been

seen by almost no one. In the new St. Peter's Basilica,

designed by Michelangelo, the cloth was kept locked behind

three bars. And "over the course of time, the image

became very faint," Cardinal Francesco Marchisano,

the Archpriest of the Basilica, told me in a letter on

May

31, 2004

.

But in fact, it has not only grown faint, most probably it is

also an ordinary dummy (or hoax / or fake). It hasn’t only

become virtually invisible to us: there is not a single

reliable photograph of the image either. Devotees of icons of

Christ were for this reason in recent times often directed to

another image in the sacristy of the Popes, the so-called Abgar

portrait from

Edessa

,

which is said to be the oldest painting of Jesus in the world

-- and it looks it.

This

image has, over the centuries, become almost black, like many

ancient paintings, executed in tempera on linen. The

"true image" of Christ, however, was made with no colors

at all. Before it came to

Rome

,

it was in

Constantinople

,

and before that in the

Middle

East

.

A Syrian text from Kamulia in

Cappadocia

from the 500s tells us that the image was "drawn out of

the water" and "not painted by human hand." But

not before this image came to

Rome

,

curious pilgrims were drawn to it as to a magnet.

This

image has, over the centuries, become almost black, like many

ancient paintings, executed in tempera on linen. The

"true image" of Christ, however, was made with no colors

at all. Before it came to

Rome

,

it was in

Constantinople

,

and before that in the

Middle

East

.

A Syrian text from Kamulia in

Cappadocia

from the 500s tells us that the image was "drawn out of

the water" and "not painted by human hand." But

not before this image came to

Rome

,

curious pilgrims were drawn to it as to a magnet.

With

twigs/branches of palm-trees Pilgrims to

Jerusalem

decorated themselves on their return in the first half of the

second millennium. The sign of the pilgrims on the route to

Santiago de Compostela is even

today a shell. Pilgrims to

Rome

,

however, adhered miniature images of Christ unto their cape on

their way home: little pictures of the "Sancta Veronica Ierosolymitana":

the holy Veronica from

Jerusalem

.

The foundation of the new St. Peter's Basilica was thus laid

by Pope Julius II as the foundation also for a great treasure

chamber to hold and protect this unique treasure.

But,

during the construction of the new basilica – which had been

highly disputed and controversial in those times - the veil of

Veronica mysteriously disappeared from

Rome

.

The only remnant of the veil that remains today in Rome is a

Venetian frame with a pane of old, cracked glass, still on

display in St. Peter's treasury. But the veil was not lost.

For 400 years the most important relic of Christendom, before

which the Emperor of Byzantium knelt once a year, held between

two panes of glass, has been on display in a tiny Capuchin

church which is completely empty for many hours each day, in

the town of

Manoppello

,

in

Italy

's

Abruzzi

region. It is the missing role model for the entire western

civilisation. Today finally it must be regarded as

rediscovered. It fades away against light, it darkens in

shadow, yet it endures through the centuries, unchanging.

It

shows the bearded face of a man with side-curls (jewish

peyoth), whose nose has been hit

like that of a detainee in the Abu Ghreib

prison. The right cheek is swollen, the beard partly ripped

off. The forehead and lips have on them hints of pink,

suggesting freshly healed wounds. Inexplicable peace fills the

gaze out of the wide open eyes. Amazement,

astonishment, surprise. Gentle

compassion. No despair, no pain, no wrath. It is like

the face of a man who has just awakened to a new morning. His

mouth is half open. Even his teeth are visible. If one had to

give a precise phrase to the vowel and word the lips are

forming, it would be just a soft "Ah."

All

proportions of the image show 1 : 1

the measurements of a human face, filling the center

of 17 by 24 centimeter cloth. The

flimsy veil is transparent, like a silk stocking. The image is

less like a painted picture than a large slide. Held up to the

light, it is transparent. In the shadow, without light, it

becomes almost slate grey. A tiny, broken piece of crystal

rests in the lower right corner of the frame. In the light of

light bulbs, the delicate cloth is gold and honey-colored,

just as the face of Christ was described by Gertrud of Helfta

in the 13th century. For only in the light and contrast, does

the fine cloth show the countenance in three-dimensional,

almost holographic clarity – and from both sides, only back

to front (“the wrong way round”). It seems so finely

woven, that it might fit into a walnut shell if it were folded

tightly.

Professor

Donato Vittori

of the

University

of

Bari

and Professor Giulio Fanti

of the

University

of

Padua

have discovered, through microscopic examinations, that there

is no trace of color or paint at

all on the entire cloth. Only in the black pupils of both eyes

does there appear to be a slight scorching of the threads, as

if they had been heated.

All

of this cannot be considered a completely fresh discovery. The

farmers and fisherman of the

Adriatic

from

Ancona

to Tarento have revered this veil

for centuries as the "Holy Face," ("Il Volto

Santo"). It is said in Manoppello

that "angels" brought the cloth to them 400 years

ago (citing in this regard an old report). That may be. But it

is more likely that some rascals, too, slipped in beneath the

angels' wings, who simply swiped and robbed the relic -- in

probably the most impudent rascal piece of the entire Baroque

era (which had never been poor of rogues and villains)

. The broken crystal in the old frame of Veronica's

Veil in St. Peter's

Basilica treasury seems to sing one verse of this larger song

until today. The story has elements of a farce, of a crime

thriller, of a detective story, of a drama -- and of a fifth

gospel for our image-obsessed age.

But

when Professor Heinrich Pfeiffer of Rome's Gregorian

University for the first time brought to the attention of the

scholarly world that the Manoppello

Countenance most likely had to be considered as the ultimate

point of reference for the oldest pictures of Christ, both in

the East and in the West, these sensational news appeared in

the back pages of the world press under the category

“miscellaneous”. This happened about a decade ago. And no

matter how precisely Pfeiffer, a German scholar of early

Christian art, had investigated to prove that the image in Manoppello

must be acknowledged as a “mother of images” for the

entire Christian iconography, his colleagues, too, along with

many prelates and cardinals in the Vatican shook the heads

over the exuberant professor's imagination.

Sister

Blandina Paschalis Schlömer,

a German Trappist nun, pharmacist

and icon painter, was the one who had initiated Pfeiffer's

research and conclusions. She had discovered, years before,

after painstaking comparisons of the image on the Manopello

cloth and the face of the man depicted on the Shroud of Turin,

that the two images were identical: that they were both

displaying the very same person. Every detail of both faces

was exactly congruent: the same size and shape, the same

wounds. The one difference: on the Shroud, the wounds are

still open. On the cloth of Manoppello,

the wounds have closed.

These

results, either, did not persuade or convince other scholars

of the authenticity of the image of Manoppello.

Quite the opposite. The chief

objection was simple and categorical: that the Manoppello

image had been painted. The image was just too clear and fine

for it not to have been painted, they argued. The eyes, the

eyelashes (not visible until photo enlargements were made),

the tear sacks in the eyes, the whiskers, the teeth (!), all

that simply could not have appeared without the delicate hand

of a master artist. In short, the Manoppello

image was not a model, but a careful copy of other copies of

an unknown original - or even of the original on the Turin

Shroud.

A

question seldom posed up to now, but a crucial one, concerns

the fabric itself. By its consistency, it seems like colored

nylon -- though nylon was not invented 400 years ago. What is

it, then? Cotton, wool, linen? No,

all are much too thick to allow this immaterial transparency. Even

silk does not permit this. Meanwhile, the Capuchins of Manoppello

have decided to wait before subjecting the cloth to any

scientific or chemical tests, or even to take it out of the

glass where it has been held for 400 years.

"Not

necessary!" Father Germano,

the last Guardian of the cloth, said to me a few weeks ago.

"Science will progress to meet us. It develops so fast,

that we only need to wait." He is probably correct. Many

photos, which I took in recent months with my digital camera,

show the fabric in a way I have never seen in other photos.

What could this cloth be? In the Gospel of John, John speaks

of two cloths found in the empty tomb of Christ in

Jerusalem

.

According to that source, Peter and "the other young

man" (probably John himself) ran toward the tomb in the

early dawn of Easter Sunday. John ran faster and reached the

tomb first. John writes: "They both ran, but the other

disciple outran Peter and reached the tomb first; and stooping

to look in, he saw the linen cloths lying there, but he did

not go in. Then Simon Peter came, following him, and went into

the tomb; he saw the linen cloths lying, and the cloth, which

had been on his head, not lying with the linen cloths but

rolled up in a place by itself. Then the other disciple, who

reached the tomb first, also went in, and he saw and

believed."

It

is this second cloth, the small one which had been on Christ's

head, which the inhabitants of Manoppello

have always regarded as the one they have in their town. This

cloth is sometimes known as the "sweat cloth." The Manoppello

cloth, however, has not a drop of sweat detectable on it. But

then, the cloth is so fine, it cannot hold even a single drop

of blood or sweat.

Rome

,

1.

September 2004, Fiumincino

airport. A fresh breeze from the nearby

Mediterranean

cools the late summer morning. The clock in Hall A reads

7:35

a.m.

,

as the Alitalia flight 1570 from

Cagliari

touches down outside on the runway. When Chiaro

Vigo crosses the barrier, I

recognize her immediately, although I had never seen her

before. Her fingernails are spindles, long and pointed. Pier

Paolo Pasolini might have cast her

as the star in any of his films. She comes from the small

island

of

Sant'Antioco

off the coast of

Sardinia

,

where she is the last living byssus

weaver on earth, heir to an unbroken tradition dating to

ancient times.

"To our people, byssus is a

holy fabric," she says in the car. What does she mean,

"Our people?" Isn't her island simply part of

Sardinia

?

No, she laughs roughly. On her island, Sardinian and Italian

are spoken, but they also know many Aramaic songs, for the

population is descended from Chaldaeans

and Phoenicians. They trace their art of byssus

production to the Princess Berenike,

one of Herod's daughters, who was a lover of the Emperor

Titus, after he had destroyed

Jerusalem

.

-- Then she held out to me a bundle of unspun,

raw byssus. In the morning light,

it shone more finely than angel hair. The gold of the seas! In

her hand, it shone like bronze in the sun. The material is

produced from threads a certain kind of sea mussels (“pinna

nobilis”) generate to cling to

the ground. Every May Chiara Vigo

dives under full moonlight five meters deep in the sea to

collect and harvest them – before there are combed, then

spun and woven into a most precious fabric.

Byssus

was the most costly fabric in the ancient world. It has been

found in the tombs of Egyptian Pharaohs, and it is mentioned

often in the Bible, where it is said to be obligatory for the

carpets of the Holy of Holies and for the "Ephod",

the vestment of the high priest. Steeped in lemon, it becomes

golden. In former times, soaked in cow's urine, it became

paler and brighter. We fly down the highway toward Manoppello.

Sister Blandina awaits us on the

hill just above the church, where she lives. As we walk up the

central aisle, the "Holy Face" appears to be a

milky, rectangular communion host above the altar. A

cross in the window gleems

(shimmers, shines) from the back of the choir right through

the veil. After we climb the steps behind the altar and

draw close to the image, Chiara Vigo

falls to her knees. She has never seen a veil so finely woven.

"It has the eyes of a lamb," she says and crosses

herself. "And a lion."

And then: "That is Byssus!"

Chiara Vigo

says it once, twice, thrice. Byssus

can be dyed with purple, she had explained to me in the car.

"Yet Byssus cannot be painted

on. It is simply not possible. O Dio!

O Dio mio

(Oh my God! Oh my God!")!" "That is Byssus!"

This means: it cannot be any sort of painted picture. Thus,

the image on the veil is something else. Something

that transcends any picture.

Paul

Badde, 29. September 2004

(Feast

of the Archangels Michael, Gabriel & Raphael)